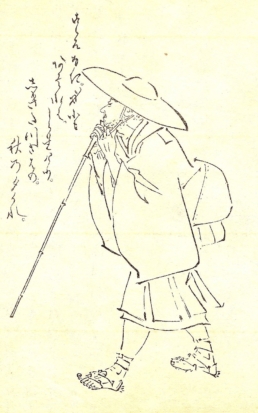

When the Japanese poet Matsuo Bashō (1644—1694) set out from Tokyo in the late spring of 1689 on a trek to the sparsely populated north of Japan’s main island of Honshū (also called “Oku” – “Interior” or “Hinterland”), he was 46 years old and already famous among contemporaries as a master of “renku” poetry (also “haikai no renga” or “renga”), a precursor of the haiku verse form in which several poets take turns of producing their lines, thus completing the poem together.

It was to be Bashō’s third great journey, and there can be no doubt that he undertook it in the spirit of the “angya” (literally: “to walk”) – Zen Buddhist walking retreats in which, although the path (more precisely: each individual step) is as important as the destination, the wandering monk nevertheless never lingered long or even wandered aimlessly, but concentrated on completing a strict daily workload and heading for certain meaningful waypoints – for example, holy shrines, but also natural monuments. In 150 days, Matsuo Bashō covered a distance of 2,400 kilometers, an average of 16 kilometers a day, in sometimes impassable, snow-covered mountainous areas and in all weathers.

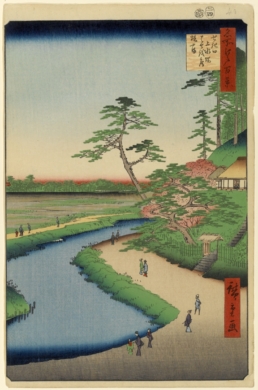

Matsuo Bashō described his trek through the north of the Honshū Peninsula in a famous travelogue entitled Oku no Hosomichi (“The Narrow Path to the Interior” or “The Narrow Road to the Hinterland”). Even before he set out, he had “dreamed of the full moon rising over the pine islands of Matsushima,” Bashō wrote in it. Indeed, for a sophisticated, established poet at the time, such an “angya” wandering trip offered another invaluable incentive: the opportunity for “uta-makura,” a special concept in Japanese poetry. Uta-makura referred to scenic “poem places” (such as the pine islands of Matsushima, which are ranked among the most beautiful landscapes in Japan) where earlier poets had composed famous verses, so that these places had found their way into classical Japanese literature. Many later poets imposed upon themselves the duty of making pilgrimages to these sites, emulating the poetic moods of their predecessors, and ultimately keeping the tradition alive through their own poems.

When the Japanese poet Matsuo Bashō 1644—1694) set out from Tokyo in the late spring of 1689 on a trek to the sparsely populated north of Japan’s main island of Honshū (also called “Oku” – “Interior” or “Hinterland”), he was 46 years old and already famous among contemporaries as a master of “renku” poetry (also “haikai no renga” or “renga”), a precursor of the haiku verse form in which several poets take turns of producing their lines, thus completing the poem together.

It was to be Bashō’s third great journey, and there can be no doubt that he undertook it in the spirit of the “angya” (literally: “to walk”) – Zen Buddhist walking retreats in which, although the path (more precisely: each individual step) is as important as the destination, the wandering monk nevertheless never lingered long or even wandered aimlessly, but concentrated on completing a strict daily workload and heading for certain meaningful waypoints – for example, holy shrines, but also natural monuments. In 150 days, Matsuo Bashō covered a distance of 2,400 kilometers, an average of 16 kilometers a day, in sometimes impassable, snow-covered mountainous areas and in all weathers.

Matsuo Bashō described his trek through the north of the Honshū Peninsula in a famous travelogue entitled Oku no Hosomichi (“The Narrow Path to the Interior” or “The Narrow Road to the Hinterland”). Even before he set out, he had “dreamed of the full moon rising over the pine islands of Matsushima,” Bashō wrote in it. Indeed, for a sophisticated, established poet at the time, such an “angya” wandering trip offered another invaluable incentive: the opportunity for “uta-makura,” a special concept in Japanese poetry. Uta-makura referred to scenic “poem places” (such as the pine islands of Matsushima, which are ranked among the most beautiful landscapes in Japan) where earlier poets had composed famous verses, so that these places had found their way into classical Japanese literature. Many later poets imposed upon themselves the duty of making pilgrimages to these sites, emulating the poetic moods of their predecessors, and ultimately keeping the tradition alive through their own poems.

One such predecessor, in whose footsteps Matsuo Bashō followed and from whom he drew inspiration, was Hōshi (1118—1190), a Zen Buddhist monk and poet who 500 years earlier had spent almost his entire life wandering through northern Honshū and living in hermitages on various mountains. The name Hōshi meant both “star” and (Buddhist) “priest” or “monk.” But Hōshi had also acquired a pen name: “Saigyō” (“Journey to the West”), a significant reference to the Amitābha Buddha and the “Western Paradise” of Pure Land Buddhism. Many of these monks wished nothing more than to die facing West, to greet the Buddha. Matsuo Bashō supposedly wished nothing more than to discover the truth about the human soul and its travels through space and time.

The title of Bashō’s travelogue represented of course both the actual journey into the rugged interior of his country Japan, and the symbolic journey into the poet’s own interior. Any geographical interior a traveler discovers – he always unfailingly discovers the interior of his own soul. The art of making a home anywhere he travels, consists in becoming at home in his own soul. He doesn´t have to be distracted by apparent distances in space or in time, in height or in depth – every path leads to the same spot anyway. As Japanese Haiku expert Nobuyuki Yuasa noted, “Oku no Hosomichi is Bashō’s study of eternity, and in so far […] it is also a monument he has set up against the flow of time.”

We find the reference to eternity right at the beginning of Oku no Hosomichi: “The days and months travel through eternity; they come and go like the years.” The opening quotation from above is a possible translation of the third part of the second sentence:

- “[For] those who sail on ships over the water or ride on horses over the earth, …” (i.e. “[For] all travelers”)

- “…every day is a journey, …” or “…the whole of life is a journey, …” or “…the journey is the whole of life, …”

- “…and the journey itself its residence.” resp. “…and the journey itself its home.” resp. “…the journey is the home.”

An appropriate translation of the beginning of Oku no Hosomichi might thus be:

“The days and months travel through eternity; they come and go like the years. For those who spend their whole lives sailing the sea on ships or riding the earth on horses, the journey itself is life, the journey is their home.”

Die Art des Reisens, die Matsuo Basho zur Kunstform erklärt und zu vollenden versucht, ist jeder Art von stationärem Leben vorzuziehen. Was nicht vorzuziehen ist, ist irgendeine Art von Reisen. die sich schnell abnutzt, durch die man auslaugt, oder auch ganz einfach durch die man seine Humanität verliert oder nicht (wieder)findet. Matsuo Basho als humanistischer Reisender, als mitfühlender Reisender, als neugieriger Reisender, als ohne Eile Reisender, als überall Hinreisender, dem kein Ziel zu klein ist, wenn er dort nur einen Zuwachs an Humanität entweder in seinem eigenen Leben oder durch das Beispiel seines eigenen Lebens vermutet.

Wie Rebecca Solnit in A Field Guide to Getting Lost (2005) schreibt, ist das “Losgehen”, das “In die Fremde” oder “In die Irre gehen” genauso eine Kunst wie das “Wieder Heimkehren”, das “Zurückfinden”, neben die allerdings noch eine weitere Kunst tritt, nämlich das “im Unbekannten zu Hause zu sein, sodass man, wenn man sich mittendrin befindet, nicht in Panik ausbricht oder Schaden leidet: die Kunst, in der Irre zu Hause zu sein. Diese Fähigkeit ist vielleicht gar nicht so weit entfernt von Keats’ Fähigkeit, »das Ungewisse, die Mysterien, die Zweifel zu ertragen«.” Dieses Zitat des Dichters John Keats, auf das Rebecca Solnit verweist, passt exakt zum Geisteszustand Matsuo Bashōs, als dieser einige Jahrhundert zuvor “ohne alles aufgeregte Greifen nach Fakten und Verstandesgründen” (so Keats) das Ungewisse, die Mysterien und die Zweifel in seine eleganten, knappen Haikus überführte. ■

We find the reference to eternity right at the beginning of Oku no Hosomichi: “The days and months travel through eternity; they come and go like the years.” The opening quotation from above is a possible translation of the third part of the second sentence:

- “[For] those who sail on ships over the water or ride on horses over the earth, …” (i.e. “[For] all travelers”)

- “…every day is a journey, …” or “…the whole of life is a journey, …” or “…the journey is the whole of life, …”

- “…and the journey itself its residence.” resp. “…and the journey itself its home.” resp. “…the journey is the home.”

An appropriate translation of the beginning of Oku no Hosomichi might thus be:

“The days and months travel through eternity; they come and go like the years. For those who spend their whole lives sailing the sea on ships or riding the earth on horses, the journey itself is life, the journey is their home.”

Wie Rebecca Solnit in A Field Guide to Getting Lost (2005) schreibt, ist das “Losgehen”, das “In die Fremde” oder “In die Irre gehen” genauso eine Kunst wie das “Wieder Heimkehren”, das “Zurückfinden”, neben die allerdings noch eine weitere Kunst tritt, nämlich das “im Unbekannten zu Hause zu sein, sodass man, wenn man sich mittendrin befindet, nicht in Panik ausbricht oder Schaden leidet: die Kunst, in der Irre zu Hause zu sein. Diese Fähigkeit ist vielleicht gar nicht so weit entfernt von Keats’ Fähigkeit, »das Ungewisse, die Mysterien, die Zweifel zu ertragen«.” Dieses Zitat des Dichters John Keats, auf das Rebecca Solnit verweist, passt exakt zum Geisteszustand Matsuo Bashōs, als dieser einige Jahrhundert zuvor “ohne alles aufgeregte Greifen nach Fakten und Verstandesgründen” (so Keats) das Ungewisse, die Mysterien und die Zweifel in seine eleganten, knappen Haikus überführte. ■

Anabasis

Matsuo Bashōs Reise von der zivilisatorisch erschlossenen Küste ins dünn besiedelte, vermeintlich gefährliche Landesinnere erinnert ein wenig an die alte antike Reise- und Erzählform der Anabasis. Anabasis bedeutet wörtlich “Hinaufmarsch” (von griechisch ana = “upward” und bainein = “to step or march”), wovon im Übrigen auch die Bezeichnung “anabatische Winde” (also auflandige Winde an Bergrücken) herrührt. In der Antike stand der Begriff Anabasis für militärische Expeditionen von der Küste ins Landesinnere, ins Hinterland. Zu den bekanntesten anabatischen Reiseberichten gehören die Anabasis des Alexander von Arrian und die Anabasis von Cyrus dem Jüngeren von Xenophon – beides antike griechische Historiker, die über berühmte Feldzüge berichteten.

- Nine Translations of the Opening Paragraph of Oku no Hosomichi

- Complete Online Edition of Oku no Hosomichi

- Matsuo Bashō (Wikipedia)

- Oku no Hosomichi (Wikipedia)

- Uta-makura (Wikipedia)

- Saigyō Hōshi (Wikipedia)

- Angya (Wikipedia)

Become Our Trail Angel

Support our work

If you are truly grateful for the impressions and inspiration you receive through travel4stories, we would be delighted if you would become one of our “Trail Angels” and help fill our little digital piggy bank with travel karma. This project is only possible thanks to supporters like you. Even small amounts carry us over long distances.

What goes around, comes around… As a proof, I say thank you for every single donation with a beautiful postcard—mailed directly to your (or a friend´s) physical mailbox. All you have to do is fill in the desired address. Recurring donors get multiple postcards per year. If you don´t need/want postcards, you can still use the donation form and just ignore the address lines.

*Click on the button above and follow three simple steps in the pop-up form of our trusted partner donorbox. Checkout is possible via credit card and PayPal. You can select a one-time or a recurring donation. For recurring donors, a donor account is created automatically. Account setup info will be mailed to you. You have full control over your donation and you can cancel anytime. Your personal data is always secure.

If you prefer donating in other ways, you can become our Patreon, or support us directly via PayPal.

The possibilities to support us with good travel karma are near endless.

Please click here to see them all.

We would like to thank all our supporters from the bottom of our hearts!

Read Great Stuff

Discover Stories & Images, Tours & Trails, Travel Series, and More...

Nothing found.

Comments

We´re curious what you think