Quotes

From Travellers & Soul-Searchers

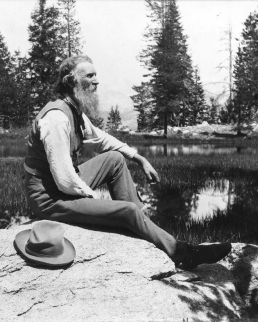

— John Muir

The Scottish-born American naturalist and author John Muir (1838—1914) wrote this famous line in his panegyric about the Yellowstone National Park, which had been established in 1872 as the first national park in both the U.S. and the world. Muir himself played a major role in the creation of another protected area in 1890, Yosemite National Park in California’s Sierra Nevada, where he had lived and researched for many years, beginning as a sheep herder just four years after the Yosemite Grant (1864), which had granted legal protected status to a geographic area for the first time in U.S. history.

The idea of a national or even international common ownership of a region worthy of protection, with the strict prohibition of private land ownership and a strong imperative of nature conservation, contrasts strikingly with the often brutal history of these regions, from the expulsion of indigenous peoples to the unrestrained exploitation of resources. It also anticipates later ideas of biosphere reserves and UNESCO World and Natural Heritage Sites, and points a way to the future when humanity may have to take even more drastic measures to save its livelihoods. The idea that nature, and even more so wilderness, are entities worthy of protection was far from self-evident in Muir’s day, and he is considered one of the most important of the modern Western and white fathers of this idea because of his extensive body of work and because of his incorruptible enthusiasm.

Interestingly, Muir was never particularly satisfied with his writing. He regarded prose and books as tending to be unsuited to express the things he wanted to express – insights he had gained through years of living in mountains and valleys, under clouds and trees, by rivers and lakes. He wrote: “No amount of word-making will ever make a single soul to ‘know’ these mountains. One day’s exposure to mountains is better than a cartload of books.” His quest for simplicity and his struggle for words reflect the eminent quandary of all nature and travel writers: how to clothe something as overwhelming as nature and, at the same time, something as ephemeral as one’s sojourn in it in something more than a stammer. Muir somehow steered clear of that cliff. The extended quote goes like this:

“Walk away quietly in any direction and taste the freedom of the mountaineer. Camp out among the grasses and gentians of glacial meadows, in craggy garden nooks full of nature’s darlings. Climb the mountains and get their good tidings, Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their own freshness into you and the storms their energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves.”

Sources:

- The Yellowstone National Park, in: The Atlantic Monthly, volume LXXXI, number 486 (April 1898) pages 509-522 (at pages 515-516);

- modified slightly and reprinted in “Our National Parks” (1901), chapter 2: The Yellowstone National Park

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Muir

- Jack Kerouac

This is a quote from Some of the Dharma (written between 1953 and 1956), a non-fictional, autobiographical collage of notes on the meaning of life, the art of writing, and more. Jack Kerouac (1922—1969) was deeply involved with Buddhism during that period, which was reflected in his much more famous work of fiction, The Dharma Bums (1958). In the latter, a first-person narrator named “Ray Smith” (an alter ego of Jack Kerouac) describes his memories of a friend named “Japhy Ryder”, real-life Beat poet Gary Snyder, who had first introduced Kerouac to Zen Buddhism in the early 1950s. In general, Buddhism as an additional anarchist source of inspiration (along with free jazz, bebop, alcohol, drugs, and more) had caught the attention of the Beat generation.

Unlike Kerouac’s great success On The Road (1957) – arguably one of the most famous travel books of the 20th century – in which the journey sometimes seems the only meaning of life – always a little too crazy, a little too fast, a little too enigmatic – The Dharma Bums strikes a more reflective tone. Here, life is a journey, not the journey the life. The title alone is a masterpiece. The content wants to be a Zen work of art itself. In the novel, as probably in real life, both characters vacillate between the simple, sober, secluded life of wandering monks in the mountains and in nature, and the exciting, ecstatic social life in jazz clubs and literary cafes of big cities. The dissolution of dualities, the spiritual quest and the departure from social conventions are central themes in the books as well as in the life of the author Jack Kerouac.

Some of the Dharma, from which the above quotation is taken, represents, so to speak, the intellectual basis on which the aforementioned novels were written; the breeding ground from which they grew. It is more of a mixture of diary notes and philosophical notebook. It provides much more background on author Jack Kerouac than all of his fictional works combined. It is an excellent document of a spiritual and artistic quest, a kind of meta-fiction of the author about himself – extremely dense, full of symbolism, full of insights, full of doubts. A search for enlightenment. A search for the right words.

Gary Snyder also inspired Kerouac to work as a “fire lookout” in the mountains. In the summer of 1956, he began his lonely watch on a wooden tower on Desolation Peak in the North Cascades of Washington State. His only reading during those long months was the Diamond Sutra of Mahayana Buddhism, which Kerouac had first read a year earlier. Like a true Buddhist monk in retreat, he recited the sutra according to a strict schedule in weekly cycles, thus emptying his mind. Quite explicitly, he hoped for a spiritual vision.

There is this cliché about Zen Buddhism, namely that true masters eventually run out of words when they have left all dualities behind, and that they not infrequently fall completely silent. Whether Jack Kerouac, who obviously did not fall silent, should therefore be denied Zen mastery altogether, or whether, on the contrary, he succeeded masterfully in putting the dissolution of dualities into “simple words”, everyone may decide for himself.

The original quote in Some of the Dharma goes actually a bit different: “Soon I’ll find the right words, they’ll be very simple…”

Sources:

- Excellent Overview over Kerouacs Buddhist reflections: https://tricycle.org/magazine/some-dharma/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_Kerouac

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Dharma_Bums

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/On_the_Road

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gary_Snyder

This is a quote from Some of the Dharma (written between 1953 and 1956), a non-fictional, autobiographical collage of notes on the meaning of life, the art of writing, and more. Jack Kerouac (1922—1969) was deeply involved with Buddhism during that period, which was reflected in his much more famous work of fiction, The Dharma Bums (1958). In the latter, a first-person narrator named “Ray Smith” (an alter ego of Jack Kerouac) describes his memories of a friend named “Japhy Ryder”, real-life Beat poet Gary Snyder, who had first introduced Kerouac to Zen Buddhism in the early 1950s. In general, Buddhism as an additional anarchist source of inspiration (along with free jazz, bebop, alcohol, drugs, and more) had caught the attention of the Beat generation.

Unlike Kerouac’s great success On The Road (1957) – arguably one of the most famous travel books of the 20th century – in which the journey sometimes seems the only meaning of life – always a little too crazy, a little too fast, a little too enigmatic – The Dharma Bums strikes a more reflective tone. Here, life is a journey, not the journey the life. The title alone is a masterpiece. The content wants to be a Zen work of art itself. In the novel, as probably in real life, both characters vacillate between the simple, sober, secluded life of wandering monks in the mountains and in nature, and the exciting, ecstatic social life in jazz clubs and literary cafes of big cities. The dissolution of dualities, the spiritual quest and the departure from social conventions are central themes in the books as well as in the life of the author Jack Kerouac.

Some of the Dharma, from which the above quotation is taken, represents, so to speak, the intellectual basis on which the aforementioned novels were written; the breeding ground from which they grew. It is more of a mixture of diary notes and philosophical notebook. It provides much more background on author Jack Kerouac than all of his fictional works combined. It is an excellent document of a spiritual and artistic quest, a kind of meta-fiction of the author about himself – extremely dense, full of symbolism, full of insights, full of doubts. A search for enlightenment. A search for the right words.

Gary Snyder also inspired Kerouac to work as a “fire lookout” in the mountains. In the summer of 1956, he began his lonely watch on a wooden tower on Desolation Peak in the North Cascades of Washington State. His only reading during those long months was the Diamond Sutra of Mahayana Buddhism, which Kerouac had first read a year earlier. Like a true Buddhist monk in retreat, he recited the sutra according to a strict schedule in weekly cycles, thus emptying his mind. Quite explicitly, he hoped for a spiritual vision.

There is this cliché about Zen Buddhism, namely that true masters eventually run out of words when they have left all dualities behind, and that they not infrequently fall completely silent. Whether Jack Kerouac, who obviously did not fall silent, should therefore be denied Zen mastery altogether, or whether, on the contrary, he succeeded masterfully in putting the dissolution of dualities into “simple words”, everyone may decide for himself.

The original quote in Some of the Dharma goes actually a bit different: “Soon I’ll find the right words, they’ll be very simple…”

Sources:

- Excellent Overview over Kerouacs Buddhist reflections: https://tricycle.org/magazine/some-dharma/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_Kerouac

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Dharma_Bums

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/On_the_Road

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gary_Snyder

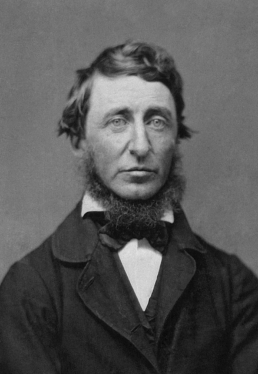

- Henry David Thoreau

The Scottish-born American naturalist and author, who lived from 1838 – 1914, wrote this famous line in his panegyric about the Yellowstone National Park (USA). The extended quote goes like this:

“Walk away quietly in any direction and taste the freedom of the mountaineer. Camp out among the grasses and gentians of glacial meadows, in craggy garden nooks full of nature’s darlings. Climb the mountains and get their good tidings, Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their own freshness into you and the storms their energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves. As age comes on, one source of enjoyment after another is closed, but nature’s sources never fail.”

Sources:

- The Yellowstone National Park, in: The Atlantic Monthly, volume LXXXI, number 486 (April 1898) pages 509-522 (at pages 515-516);

- modified slightly and reprinted in “Our National Parks” (1901), chapter 2: The Yellowstone National Park

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Muir

- Matsuo Bashō

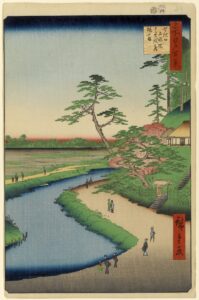

When the Japanese poet Matsuo Bashō 1644-1694) set out from Tokyo in the late spring of 1689 on a trek to the sparsely populated north of Japan’s main island of Honshū (also called “Oku” – “Interior” or “Hinterland”), he was 46 years old and already famous among contemporaries as a master of “renku” poetry (also “haikai no renga” or “renga”), a precursor of the haiku verse form in which several poets take turns of producing their lines, thus completing the poem together.

It was to be Bashō’s third great journey, and there can be no doubt that he undertook it in the spirit of the “angya” (literally: “to walk”) – Zen Buddhist walking retreats in which, although the path (more precisely: each individual step) is as important as the destination, the wandering monk nevertheless never lingered long or even wandered aimlessly, but concentrated on completing a strict daily workload and heading for certain meaningful waypoints – for example, holy shrines, but also natural monuments. In 150 days, Matsuo Bashō covered a distance of 2,400 kilometers, an average of 16 kilometers a day, in sometimes impassable, snow-covered mountainous areas and in all weathers.

Matsuo Bashō described his trek through the north of the Honshū Peninsula in a famous travelogue entitled Oku no Hosomichi (“The Narrow Path to the Interior” or “The Narrow Road to the Hinterland”).

Even before he set out, he had “dreamed of the full moon rising over the pine islands of Matsushima,” Bashō wrote in it. Indeed, for a sophisticated, established poet at the time, such an “angya” wandering trip offered another invaluable incentive: the opportunity for “uta-makura,” a special concept in Japanese poetry. Uta-makura referred to scenic “poem places” (such as the pine islands of Matsushima, which were among the most beautiful landscapes in Japan) where earlier poets had composed famous verses, so that these places had found their way into classical Japanese literature. Many later poets imposed upon themselves the duty of making pilgrimages to these poem sites, emulating the poem moods of their predecessors, and ultimately keeping the tradition alive through their own poems.

One such predecessor, in whose footsteps Matsuo Bashō followed and from whom he drew inspiration, was Hōshi (1118-1190), a Zen Buddhist monk and poet who 500 years earlier had spent almost his entire life wandering through northern Honshū and living in hermitages on various mountains. The name Hōshi meant both “star” and (Buddhist) “priest” or “monk.” But Hōshi had also acquired a pen name: “Saigyō” (“Journey to the West”), a reference to the Amitābha Buddha and the “Western Paradise” of Pure Land Buddhism.

The title of Matsuo Bashō’s travelogue represented both the actual journey into the rugged interior of Japan and the symbolic journey into the poet’s own interior. Any geographical interior a traveler discovers – he always unfailingly discovers the interior of his own soul. The art of making a home anywhere you go consists in making a home within yourself. Just don´t be distracted by apparent distances in time, in space, or in depth – they all lead you to the same spot. As Japanese Haiku expert Nobuyuki Yuasa noted, “Oku no Hosomichi is Bashō’s study of eternity, and in so far […] it is also a monument he has set up against the flow of time.”

We find the reference to eternity right at the beginning of Oku no Hosomichi: “The days and months travel through eternity; they come and go like the years.” The opening quotation from above is a possible translation of the third part of the second sentence:

- “[For] those who sail on ships over the water or ride on horses over the earth, …” (i.e. “[For] all travelers”)

- “…every day is a journey, …” or “…the whole of life is a journey, …” or “…the journey is the whole of life, …”

- “…and the journey itself its residence.” resp. “…and the journey itself its home.” resp. “…the journey is the home.”

An appropriate translation of the entire beginning of Oku no Hosomichi might thus be:

“The days and months travel through eternity; they come and go like the years. For those who spend their whole lives sailing the sea on ships or riding the earth on horses, the journey itself is life, the journey is their home.”

Quellen:

- Nine Translations of the Opening Paragraph of Oku no Hosomichi

- Complete Online Edition of Oku no Hosomichi

- Matsuo Bashō (Wikipedia)

- Oku no Hosomichi (Wikipedia)

- Uta-makura (Wikipedia)

- Saigyō Hōshi (Wikipedia)

- Angya (Wikipedia)

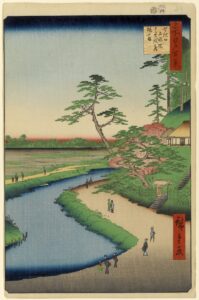

When the Japanese poet Matsuo Bashō 1644-1694) set out from Tokyo in the late spring of 1689 on a trek to the sparsely populated north of Japan’s main island of Honshū (also called “Oku” – “Interior” or “Hinterland”), he was 46 years old and already famous among contemporaries as a master of “renku” poetry (also “haikai no renga” or “renga”), a precursor of the haiku verse form in which several poets take turns of producing their lines, thus completing the poem together.

It was to be Bashō’s third great journey, and there can be no doubt that he undertook it in the spirit of the “angya” (literally: “to walk”) – Zen Buddhist walking retreats in which, although the path (more precisely: each individual step) is as important as the destination, the wandering monk nevertheless never lingered long or even wandered aimlessly, but concentrated on completing a strict daily workload and heading for certain meaningful waypoints – for example, holy shrines, but also natural monuments. In 150 days, Matsuo Bashō covered a distance of 2,400 kilometers, an average of 16 kilometers a day, in sometimes impassable, snow-covered mountainous areas and in all weathers.

Matsuo Bashō described his trek through the north of the Honshū Peninsula in a famous travelogue entitled Oku no Hosomichi (“The Narrow Path to the Interior” or “The Narrow Road to the Hinterland”).

Even before he set out, he had “dreamed of the full moon rising over the pine islands of Matsushima,” Bashō wrote in it. Indeed, for a sophisticated, established poet at the time, such an “angya” wandering trip offered another invaluable incentive: the opportunity for “uta-makura,” a special concept in Japanese poetry. Uta-makura referred to scenic “poem places” (such as the pine islands of Matsushima, which were among the most beautiful landscapes in Japan) where earlier poets had composed famous verses, so that these places had found their way into classical Japanese literature. Many later poets imposed upon themselves the duty of making pilgrimages to these poem sites, emulating the poem moods of their predecessors, and ultimately keeping the tradition alive through their own poems.

One such predecessor, in whose footsteps Matsuo Bashō followed and from whom he drew inspiration, was Hōshi (1118-1190), a Zen Buddhist monk and poet who 500 years earlier had spent almost his entire life wandering through northern Honshū and living in hermitages on various mountains. The name Hōshi meant both “star” and (Buddhist) “priest” or “monk.” But Hōshi had also acquired a pen name: “Saigyō” (“Journey to the West”), a reference to the Amitābha Buddha and the “Western Paradise” of Pure Land Buddhism.

The title of Matsuo Bashō’s travelogue represented both the actual journey into the rugged interior of Japan and the symbolic journey into the poet’s own interior. As Japanese haiku expert Nobuyuki Yuasa noted, “Oku no Hosomichi is Bashō’s study of eternity, and in so far […] it is also a monument he has set up against the flow of time.” The work begins with the sentence, “The days and months travel through eternity; they come and go like the years.” The opening quotation above is a translation possibility of the third part of the second movement:

- “[For] those who sail on ships over the water or ride on horses over the earth, …” (i.e. “[For] all travelers”)

- “…every day is a journey, …” or “…the whole of life is a journey, …” or “…the journey is the whole of life, …”

- “…and the journey itself its residence.” resp. “…and the journey itself its home.” resp. “…the journey is the home.”

An appropriate translation of the entire beginning of Oku no Hosomichi might thus be:

“The days and months travel through eternity; they come and go like the years. For those who spend their whole lives sailing the sea on ships or riding the earth on horses, the journey itself is life, the journey is their home.”

Quellen:

- Nine Translations of the Opening Paragraph of Oku no Hosomichi

- Complete Online Edition of Oku no Hosomichi

- Matsuo Bashō (Wikipedia)

- Oku no Hosomichi (Wikipedia)

- Uta-makura (Wikipedia)

- Saigyō Hōshi (Wikipedia)

- Angya (Wikipedia)

- Old Proverb

There are many versions of this very old saying. The attribution is almost impossible to make. Often it is just called an “Indian proverb”. Some attribute it the Buddha, e.g. Mandar Nath Pathak in his book Human Life and the Teachings of Buddha (1988), and Kumaraswamiji in an extended version that goes like this: “Life is a bridge, build no house upon it; it is a river, cling not to its banks; it is a gymnasium, use it to develop the mind on the apparatus of circumstance; it is a journey, take it and walk on.” Another short version is attributed to the late Sri Sathya Sai Baba: “Life is a bridge. Cross over it, but don’t build a house on it.”

English Buddhist writer Christmas Humphreys attributes the quote to the 16th century Mughal emperor Akbar the Great, or Akbar I – though he elsewhere just declares it an “old Chinese proverb”. In the city of Fatehpur Sikri, 43 km from Agra, India, in 1602 AD, Akbar the Great had built a giant gateway to the Jama Masjid mosque (still the highest gateway in the world), to commemorate his victory over Gujarat. It was called “Buland Darwaza” (“Door of victory”). Lady Dorothy Maynard Lavington Evans Daukes visited the city in the first half of the 20th century. In her book Clendon Daukes, Servant of Empire (1951) she reports on an “Arabic inscription”: “Life is a bridge, a bridge that you shall pass over. You shall not build your house upon it.” According to the Wikipedia entry of the Buland Darwaza however, the insription is in Persian, and goes like this: “Isa (Jesus), son of Mary said: ‘The world is a bridge, pass over it, but build no houses upon it. He who hopes for a day, may hope for eternity; but the world endures but an hour. Spend it in prayer for the rest is unseen.”

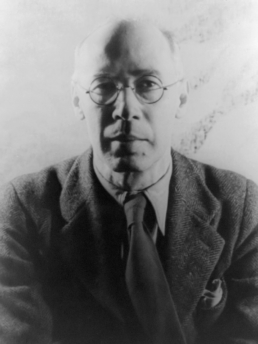

- Henry Miller

This is a quote from Some of the Dharma, a non-fictional autobiographical treatise on Buddhism, which was written between 1953 and 1956. Jack Kerouac (1922 – 1969) was heavily involved in studying Buddhism at that time – a pursuit, which led to his more famous fictional work The Dharma Bums (1958). The quote actually goes a bit different:

“Soon I’ll find the right words, they’ll be very simple…”

Sources:

- Excellent Overview over Kerouacs Buddhist reflections: https://tricycle.org/magazine/some-dharma/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_Kerouac

This is a quote from Some of the Dharma, a non-fictional autobiographical treatise on Buddhism, which was written between 1953 and 1956. Jack Kerouac (1922 – 1969) was heavily involved in studying Buddhism at that time – a pursuit, which led to his more famous fictional work The Dharma Bums (1958). The quote actually goes a bit different:

“Soon I’ll find the right words, they’ll be very simple…”

Sources:

- Excellent Overview over Kerouacs Buddhist reflections: https://tricycle.org/magazine/some-dharma/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_Kerouac

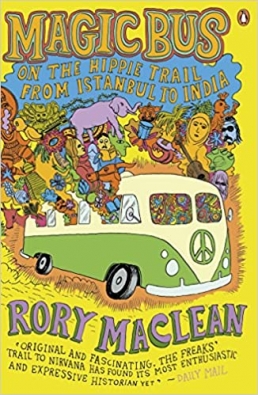

- Rory MacLean

Rory MacLean (* 1956) is a British-Canadian historian and travel writer. The quote is from the beginning of his fictional road trip Magic Bus (2006) along the famous overland ‘hippie trail’ from Europe via Turkey, Iran, and Afghanistan to India and Nepal. It´s a vivid diary of an adventure through place and time, and holds some remarkable encounters with veterans of the trail during the 1960s and early 1970s, as well as contemporary locals along it. The book includes some excellent travel description of places like Istanbul, Cappadocia, Tehran, Mashhad, Kabul, and others.